If you find yourself in a local gallery or venue, admiring a bold watercolor of animals or flowers, there’s a good chance you’ve come across a distinctive painting by Stillwater artist Edie Abnet.

It’s an experience that’s familiar to Tracy Mazanec, former owner of Tamarack Gallery in Stillwater. The fine art purveyor began showcasing the work of the accomplished local artist almost three decades ago. According to Mazanec, Abnet’s watercolors are well recognized. The medium-size tableaus offer abstract representations of natural subjects native to this region, with a preponderance of birds and flowers, vividly lined in pastel hues like periwinkle blue.

“Her paintings are a joy for the eyes, especially in the winter months [that are] so devoid of color,” Mazanec says, describing the color-rich designs as “stunning, yet easy to read.” He also observes that Abnet’s work tends to draw particularly fervent admirers. “People don’t get just one. They buy multiple works.”

Fans of Abnet’s work can find it at Tamarack Gallery, Art Resources in Edina, International Market Square in Minneapolis and Gustaf’s Galleries in Lindstrom, Minn.

Expressing Joy

Born in St. Paul, Abnet says she was raised in a time and milieu where “going to art school was seen as becoming a beatnik.” As a young woman, she pursued a nursing degree, and then went on to exercise that vocation for the next 30 years, even as her career as an artist took off. Neither motherhood nor a day job could come between Abnet and her craft. As the ardent nature-lover says, “painting is a vehicle for expressing the joy I feel in the world.” Recently retired from the healthcare profession, the 67-year-old artist still spends four to five consecutive hours working in the studio during most days of the week, beginning early in the morning when the natural light is best.

Abnet took studio art classes at Gilcrest Art Center in Tulsa, Okla., in 1967, and at the University of Minnesota from 1968 to 1971. She adopted watercolor, partly because she developed an allergic reaction to oil paints and was wary of using them around her young children. Watercolor had the advantage of feeling “like an extension of drawing,” Abnet says, and lent itself well to the blend of opaque strokes and translucent washes that define her work.

“At the time, watercolor societies demanded paintings to be strictly translucent. My feeling was always, why should there be any restrictions on creativity?” she says. While adherents to this more traditionalist view balked at Abnet’s unusual technique, it didn’t take long before Abnet found commercial success, selling her first painting before the age of 25. “I started selling right away,” she says.

Throughout the course of her career, Abnet says she has produced “too many [paintings] to count.” Between about 1985 and 2005, her most prolific period, she estimates that she created 200 paintings annually, finding great inspiration in native plants and animals.

“I always looked for that ‘Georgia O’Keeffe discovers the Southwest’ moment in my life, but the truth is, when I travel elsewhere, I love what I see, but I don’t get the urge to paint; it doesn’t speak to my soul. Minnesota is my muse,” Abnet says.

While the flora and fauna in her backyard serve as inspiration, Abnet does not paint from life, but rather uses photographs and sketches for reference. She produces her work in series, with four to five pieces in progress at any given time. While watercolor and gouache sticks are her staple media, she also works in acrylic paints from time to time. “You have to challenge the gray matter,” she says. Because her wet-on-wet technique results in “lots of standing water,” Abnet works sitting down, and always in her studio. “When I was younger, I would go and sit on the roof of my car and draw. Not anymore,” Abnet says. “No, I’m not a plein air painter. I’m far too easily distracted. I would just end up wandering off, following some bug.”

Abnet always has been mindful of her audience, as her desire to honor nature through art is accompanied by an equally strong desire to share that appreciation with others. For this reason, she chooses to paint subjects such as birds, horses and flowers that are popular with her buyers. In her view, “[Selling art is not] about making money, [but instead] a way of connecting with people. For me, that’s pretty much the definition of art. It’s like a performance, in that sense.”

Painter & Potter

In her earlier painting days, Abnet and several friends created a market for their work by organizing art and craft fairs in and around Stillwater—a precursor to the thriving art scene we know today. One enduring legacy of that time is the Marine Art Fair, an annual gathering of more than 100 local artists and craftsmen, which will celebrate its 42nd anniversary in September. It was through the Marine Art Guild that Edie first met a renowned potter named Richard Abnet, who quickly became a friend and, eventually, her husband.

“He was essentially a farm boy,” Abnet says. “His family had no idea what he was doing with his art. Even when he graduated and had his master’s [degree], they were still asking him, ‘Are you still doing that potting thing?’ They thought he was nuts.”

Abnet describes her late husband, who passed away in 2011, as “a human dynamo.” In the 1960s, as a recent college graduate with a degree in ceramics from the School for American Craftsmen at the Rochester Institute of Technology in Rochester, N.Y., Richard bought an early 20th century homestead cabin and dairy barn on a 100-acre plot of farmland, located 8 miles north of downtown Stillwater. Gradually, he transformed the barn and haymow into an art studio and gallery.

“It was his art piece,” Abnet says. “The grounds were living sculpture—always changing.”

Spinning Wheel

Today, the studio is as much a mainstay in the local arts community as its namesakes, serving as the venue for numerous educational workshops, gallery exhibits and art sales. For Abnet, the studio has been more than a workspace—she also considers it a manifestation of Richard’s belief in her art.

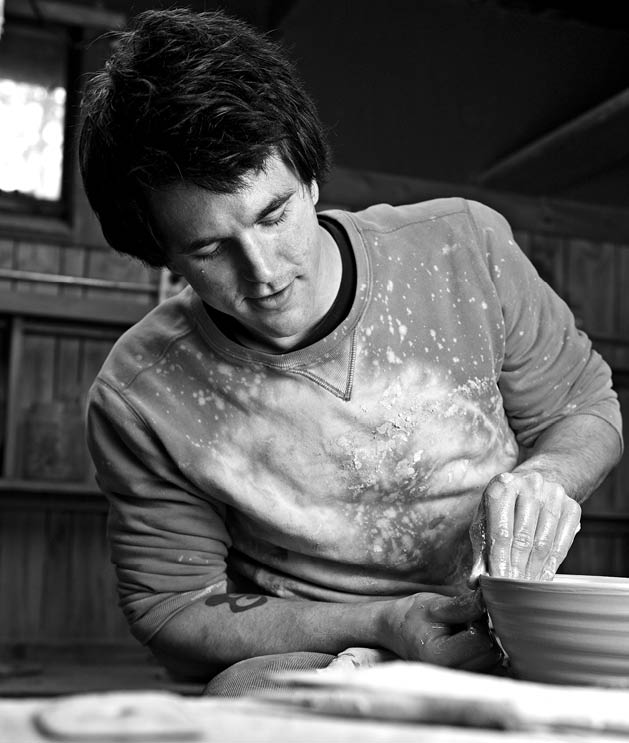

Edina native and potter Nick Earl now works in the pottery studio and lives in the refinished garage on the Abnets’ property.

Edie Abnet and Earl met through mutual friends in 2014. Abnet never wanted her husband’s equipment and supplies to go to waste and says she and Earl were “brought together by a community of people who care about the legacy of this place and all that has happened here.” She reflects on her near-instant affinity for the young potter. “I could tell he was sensitive to what this place represents [and] that his respect came naturally.”

Earl’s glazed pots line the shelves of the pottery, interspersed with unfinished vessels of Richard’s conception. “I think about the tens of thousands of pots that came before me,” Earl says. “There are little traces I try not to erase—tools or bags of clay left in a certain way. And then there’s the shard pile. For potters, that’s almost sacred.” Earl thinks about the late potter each time he adds new fragments to this physical artifact of Richard’s long and prolific career.

“I wanted art to stay in the barn as long as I was able to live there,” Abnet says. “It is wonderful having Nick’s creative energy [here]. It is fitting, and it is right. The barn studio was like an empty church—it needed worship to happen there again.”

(Artwork images courtesy of Edie Abnet)

For more information about open galleries, art sales and watercolor workshops at Abnet Farm Studio, visit their website here.